Around the end of May, my Instagram feed is usually populated with pictures from the slightly-too-cold first trips to the river and soft hues of Cannon Beach sunsets. This May was different. This May it was flooded with black squares of #BlackoutTuesday and populated with the collective grief experienced following the murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020. Every other scroll was filled with company apologies and squares that carried the message, “We’re learning and we will do better.” As a Black woman who works in brand marketing, I wanted to feel hopeful, but what I actually felt was skepticism.

Learning to be anti-racist isn’t a statement, or a public apology. It’s a process. In order to learn, one must unlearn years of implicit bias. And that is no easy task, no matter how well-meaning your intentions. The Boston Globe wrote, “Three months ago, white people were cramming as if preparing for a standardized test on systemic racism.” The wall of black-and-white posts in my feed sounded a quiet alarm in my head. It suddenly seemed as though people believed that racism could be fixed by reading alone. What was missing was an understanding of what it means to identify and dismantle biases they were unaware they held.

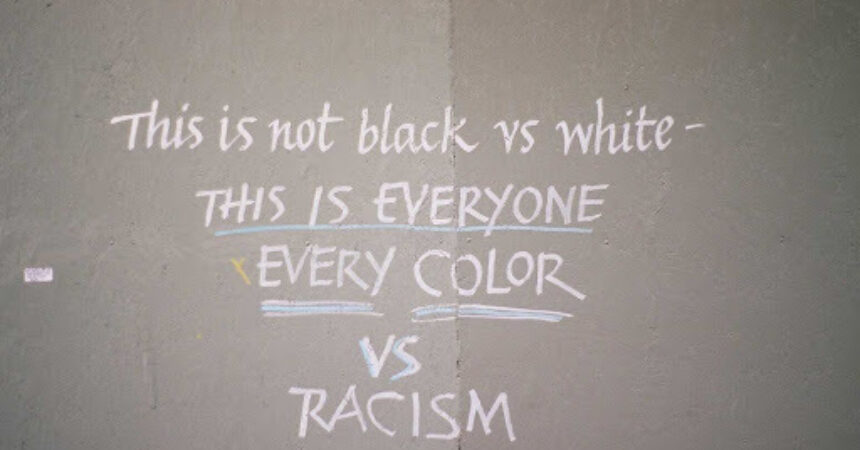

When the protests first gained momentum, I lost count of the number of fresh Black Lives Matter signs that appeared on lawns in my neighborhood. While I don’t believe they were all empty proclamations, the sudden increase felt reminiscent of 2016 when wearing a safety pin became a symbol of being a “safe” person. A piece of flair only goes so far; in order for it to carry any real power, we must also ask ourselves, “are the other ways I’m showing up for the Black community reflective of this view I have of myself?” If the answer is no, then the safety pin is less about solidarity and more about making the wearer feel good about themselves. Similarly, if behind a Black Lives Matter sign, a person isn’t interested in turning the mirror on themselves to unlearn unconscious bias or voting in ways that support the Black community, then their sign only stands for virtue signaling.

Learning to be anti-racist takes introspection, stamina, and holding yourself accountable when no one is going to pat you on the back for doing so. So are the changes that were alluded to in early June still permeating grocery stores and t-shirt companies? Or were these performative acts in order to save face? Only time will tell. From my point of view, there’s a difference I can feel between someone who authentically cares and someone who is motivated by having something to prove.

Case in point: This summer, I painted a mural in downtown Portland that represented my experience as the only Black person in my office and expressed solidarity with Black womxn who are in a similar position. The mural took seven days to paint and in that time I encountered both types of people.

There were those who treated the art downtown like a museum, who acted as if “visiting” the murals was “doing their part.” When in fact, they had missed my point entirely. And you guessed it: these were the same folks who were quick to take a picture of me in front of my mural without asking me a single question about it first. Just as an Instagram post shouldn’t be confused with fighting racism, nor should taking a walk through murals downtown.

On the other hand, there was the Black woman who walked by with her twin daughters and stopped to talk with me. As they moved onto the next panel, a portrait of Breonna Taylor, one of the girls asked, “Who is that?” and their mom explained, “This is Breonna Taylor, she was murdered by the police.” Her other daughter asked “Why did they do that?” and she responded, “Because sometimes the police kill innocent people.” Her matter-of-fact tone signaled that this wasn’t the first time they were having this conversation. Despite these girls only being around the age of five, they already had a growing body of knowledge of racism and its outcomes.

I remember my own mother teaching me to spot the prejudice that often flies under the radar, or explaining the obstacles that racism laid out when my parents were looking for their first apartment together. In our home, learning about racism wasn’t just a talk, it was a means of survival, a necessary syllabus for navigating the world.

Learning to be anti-racist comes with the hard conversations you have with yourself, and the people you love most in the world. You may eventually forget the murals downtown and the artist you met, but the honest, painful, sometimes scary conversations stick with you, building on a narrative you carry with you into your life. As Black people, we don’t have the option of perusing the art in downtown Portland like a museum and leaving when we get bored. This is our reality.

As a first step to moving away from performative anti-racism, the next time you see “Black Lives Matter,” remind yourself that “matter” is the minimum. Instead, think about how “Black lives belong.” Black lives belong in your social media feed, not just when the Black community is grieving. Black lives belong in high-level conversations at your office, not just when DEI is the topic. Black lives belong in the recommendations for your favorite restaurants, not just when supporting Black-owned businesses is trending. Black lives belong in your neighborhoods, not just in the form of yard signs that pledge your alliance. That’s where the real change begins.

Sam Reynolds is an artist, writer and Thread's resources manager. For more on what Thread is learning about the hard work of anti-racism, read “Our brilliant, wonderful, racist workplace.”